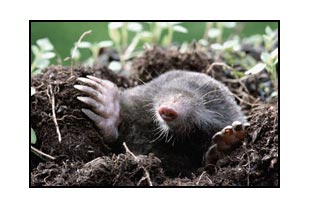

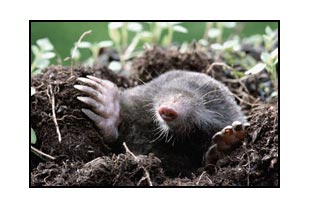

MEET THE MOLE

Although remarkable for their specialized adaptations for life underground, comparatively little is known about moles. In fact, many zoologists regard them as the least understood component of the North American fauna! However, we have unearthed an introduction to these mysterious mammals from some terrific (and often quite inventive) mole research.

Classification

Moles are fossorial (underground) mammals indigenous to Europe, Asia, and North America and belong to the family Talpidae. Of the approximately 42 recognized species worldwide, seven are found on this continent. These "new world" moles (subfamily Talpinae) are distributed widely across the United States and into parts of eastern and southwestern Canada. Populations are constrained only by natural boundaries including geographic as well as environmental obstacles such as temperature and unsuitable soil types.

Moles are frequently mistaken for pocket gophers, ground-squirrels, or mice and are commonly held as rodents. They are instead classified in the ancient order Insectivora (literally "insect-eaters"), the third largest mammalian order from which all mammals evolved. On this continent, they are unrelated to other small mammals except the shrew (family Soricidae).

Reproduction

Moles are territorial and typically live in seclusion in complex tunnel systems which they will defend aggressively from other moles, although this is rarely necessary. While burrows are generally not shared (except in areas of particularly high mole density), the territories or "homeranges" of moles do overlap. The only times when moles are deliberately colonial occur during the spring breeding season and when females are rearing the young.

Male moles begin to search out female mates (which in most species are slightly smaller) in late February through March. This breeding season is triggered by subtle changes in photoperiod (length of daylight) and fine-tuned by warming temperatures. After ensuring fertilization, male moles quickly depart to search for other receptive females.

After a gestation of approximately 42 days, the female gives birth to a single litter of two to seven moles in a grass or leaf-lined nesting chamber. This chamber is excavated five to 18 inches underground and is frequently found under a large stone, tree, or man-made obstacle such as a patio or sidewalk. Heavy mounding of soil in a closely confined area often evidences the location of the nest which is roughly the size of a quart jar. The young, born hairless, are large at birth relative to the size of the mother. Maturation occurs rapidly, and pups are weaned from their mother's milk in four to five weeks.

Shortly thereafter, the female forcibly disperses her offspring which are nearly full grown and difficult to distinguish from adults. The young establish their own tunnel systems nearby through either excavation or adoption of abandoned ones. In most of the country, this initial natal dispersal occurs from mid-April to late June and seems to be predicated on suitable soil moisture. A second dispersal period occurs in the fall with the young establishing ultimate homeranges typically within 1/4 mile of the maternal burrows. Sexual maturity is reached the following spring, perpetuating the reproductive cycle.

Life Cycle

Most mole species are unable to store either food or fat, and all moles remain active throughout the year. As the ground's surface cools and eventually freezes with the arrival of winter, moles construct deeper tunnel systems in search of food retreating from the dropping temperatures. Visible activity above ground typically diminishes, giving the false impression that moles hibernate as many other mammals. An early spring, a prolonged period of unseasonably warm weather, or an insulating snowfall often trigger new digging, and consequently results in increased levels of lawn damage.

Moles can be active at all times of the day. However, researchers have reported that their movements follow the general pattern of four hours of activity alternating with four hours of rest. The movements of moles in an area are typically synchronized and are governed by the circadian rhythms which influence all mammal species. The life span of an Eastern mole varies with longitude as well as soil type (particularly sandy soils can cause rapid tooth wear resulting in early demise). Median age has been estimated at three and a half years, but a study conducted in South Carolina turned up one senior of six!

Diet

Moles are enormously adaptable animals, and their flexible diets vary considerably with habitat. The mole's principle food source is the earthworm. Grubs, larvae, beetles, snails, slugs, and other subterranean insects effectively constitute the remainder. While moles are insectivores, they do ingest a small amount of vegetative matter. It is uncertain whether this is taken inadvertently or eaten deliberately. In any event, it does not appear to be a meaningful part of the mole's diet. Consumption of bulbs planted by homeowners is often blamed on moles, however, mice, voles, gophers, and chipmunks which have adopted abandoned mole runs are commonly the culprits.

Moles have a high metabolic rate, and must consume large quantities of food in order to meet the extreme energy requirements which excavation demands. They will usually eat an amount of food between 60-100% of their body weight daily, although it must be noted that this is not uncommon for mammals of their size. Interestingly, it is reported that captive moles provided with food will eat continuously.

Habitat

While moles inhabit diverse soil types, they prefer those that are moist, loose, and loamy. Heavy clay soil is generally avoided because digging is difficult and gas transfer may be inhibited. Moles are historically woodland creatures, however, they have adapted nicely to the lush lawns and gardens of suburbia. In fact, these areas are often preferred by moles since they harbor a larger biomass of food per acre than wilder environs. Researchers have determined that homerange size is inversely proportional to the quality of habitat. Frequent lawn watering also facilitates mole tunneling, especially during periods of drought when the soil in other areas becomes dry and hard. Generally speaking, if you have cultivated a nice lawn, you have unfortunately also created excellent mole habitat.

While the size of a specific mole's homerange is difficult to determine on inspection, it is not unusual for a tunnel system to span an acre or more in a residential setting. In a woodland environment, one study revealed that a male mole's homerange averaged 2.8 acres, while a female's covered .7 acres. However, many researchers feel that it is probably more appropriate to measure mole homerange in terms of linear feet of tunnel as opposed to square feet of ground. Mole density is usually two to three individuals per acre, however in some particularly favorable habitats, five is not uncommon.

Habits

Moles excavate complex tunnel systems, yet their tunneling can be classified into two basic types -- shallow and deep. In their search for worms and grubs just below the surface of the ground, moles create interconnected and haphazard shallow tunnels. These feeding areas are often fairly large and can be identified by a "mushy" feeling when they are stepped upon. Feeding area tunnels are rarely revisited. However, this activity can be very damaging to lawns because the grass root structures are separated from the topsoil which results in drying and eventually death. Another type of shallow construction is the surface runway. These more linear tunnels connect feeding areas and are evidenced as raised ridges in the ground.

While all unmaintained mole tunnels are eventually filled with settling soil, those on the surface are particularly short-lived and frequently collapse after a single heavy rain. In winter, shallow tunnels are abandoned in favor of deep runs until warmth returns to the uppermost layers of soil.

Deep tunnels can also take different forms. As with shallow surface runways, deep runs connect feeding areas and are generally constructed as straight paths. However, these runs are not visible on the surface as raised ridges, but are revealed as a roughly linear series of mounds. These runs are traversed several times daily.

Deep foraging tunnels are created to provide food throughout the year. These tunnels appear on the surface as large mounds clustered in a confine area. Deep foraging areas are often excavated around trees to access insect larvae which feed on the tree's root systems. Moles patrol these areas (which are often up to 24 inches in depth) frequently, and consume food which has burrowed into the tunnels. The sizable mounds which result from deep excavation cover grass on the surface, quickly killing it. This results in a pock-marked appearance to the lawn and frequently cultivates weed growth.

Moles continually add on to their tunnel complexes. The systems of burrows represent a tremendous investment of energy, and are therefore closely guarded through scent marking. Once vacated either through natural mortality, abandonment, or trapping, the tunnel system is subject to reoccupation by another mole. This recolonization occurs frequently, and in areas of high mole density, can be expected. Simply put, if a tunnel complex met the needs of one mole, it will do so for another. The significance of this behavior to the homeowner besieged by moles cannot be overstated.